Maria Pospischil

Maria Pospischil[a] (born Marie Terezie Vondřichová; 23 January 1862 – 28 May 1943), was one of the great stage actresses of the 19th century, active on German and Czech stage. She was also a writer and theatre director with several appearances in the German silent films in 1918.

Early life and career[edit]

She was born in Karlín, at that time a working class suburb of Prague. She had two sisters but not much is known about their lives (one also became an actress, another got married and lived in Mladá Boleslav[1]).

Pospischil's career began at the age of fourteen in Prague's summer vaudeville theatres, which mostly presented undemanding trivial farces. She got no formal theatre education. In 1878, she became a member of František Pokorný's touring theatre company, one of the most respected Czech touring companies, where she achieved her first significant success in the role of Gretchen in Goethe's Faust. Pokorný was the first one to mould her talent and her cast her in her fist major role. Here she met her stage mother Terezie (surnamen unknown),[2] an old experienced actress whose name has been forgotten. At this time in her career, Pospischil had a brief love affair with her colleague, the young actor Eduard Vojan. Both of them became major theatre stars in their later career.[3]

In 1879 Pokorný recommended her to the Czech Provisional Theatre. There was a vacancy in the "character type" ("emploi" in French, "Fach" in German, similar to a "stock character") of a young romantic lead after the actress Ludovika Rottová left (she ended her theatre career after getting married).

There, her talent was soon recognized by the director Antonín Pulda. He, an very intelligent and experienced teacher, brought out the performing skills of Pospischil in surprising depths. The first role he coated her in was the role of Louisa in Friedrich Schiller's drama Intrigue and Love and she rose to become one of the leading actresses of the Provisional Theatre. What was particularly praised was her sonorous voice. Pulda continued guiding her artistically for many years, they became lovers and eventually partners[4] and Pulda left his wife and son in Prague to accompany her during her engagements abroad as her impressario. It is surmised he was also her lover. Her whole career, she spoke of him as her mentor and she even went so far as to pay for his grave when he died in 1894.

Pospischil also won many admirers and patrons, including Bohemian Governor Alfred Kraus,[5]: 48 who gifted her a three-story house in the centre of Prague in admiration of her talent (when she sold the house in 1896, it was worth 46,000 guilders - i.e. eight times her annual income in 1896). Being supported by rich patrons was a common practice in German theater,[6] less common in Czech society. This earned Pospischil a dubious reputation.

In 1881, she became a member of the newly opened National Theatre in Prague (National Theatre was a successor of the Provisional Theatre). Acting at that time was divided into "characters" ("emploi" in French, "Fach" in German, similar to a "stock character"), i.e. sets of roles requiring similar physical appearance, voice, temperament, sensitivity, and similar characteristics, and actors were hired and cast according to their character type. Pospischil started as a young romantic female lead but from the very beginning she strove for a position of tragic heroine, occupied by Otilie Sklenářová-Malá and Marie Bittnerová at that time. Both held their jobs tightly, and Pospischil was kept in the field of naive lovers.

Her greatest opportunities were the role of courtesan Marion in Victor Hugo's drama Marion de Lorme and her originating of the role of Queen Elizabeth of Pomerania in Jaroslav Vrchlický's comedy A Night at Karlstein, a role that later became iconic in Czech culture, especially due to the film version. Shakespeare's Beatrice and Emma Králíčková, the female lead of Czech comedy The Eleventh Commandment are worth noting.

Although she was accused of "devouring" all the female leads of the repertoire, the rest of her thirty roles at the National Theatre were mainly supporting parts and breeches roles, as e.g. Oberon in A Midsummer Night's Dream, and still she impressed both the audience and the critics. Also, many of the shows didn't stay in the repertoire for long. Julius Zeyer's Sulamit, where Pospischil played Lilith, was performed only twice, Josef Jiří Kolár's historical drama Smiřičtí (Smirziczky family), where she played a minor role of Salomena Smirziczky, also twice.

However, her talent was widely recognized. When visiting Prague, Ludwig Chronegk, theatre director and head of the Meiningen Ensemble advised her to pursue career in Germany. Viennese comedian Alexander Girardi offered her tutoring in the rank of operetta soubrette if she decided to move to Vienna.

-

Maria Pospischil around 1884

-

Maria Pospischil as Lilithe in Julius Zeyer's Sulamit in 1884

-

Maria Pospischil as Vrchlický's Elizabeth of Pomerania (in a historically inaccurate costume)

-

Maria Pospischil around 1884

Conflict with the National Theatre director[edit]

According to many accounts, Pospischil was very stubborn, self-centered and difficult to work with. She often had the impression that she was entitled to more significant roles. The dramaturge of the theatre Ladislav Stroupežnický, who kept notes on the actors of the ensemble, noted about Pospischil: "Mercury, passion, spoiled child."[7]: 67

Both Pospischil and Pulda were not content with the authoritative leadership of the National Theatre director František Šubert who often prioritized his own protege, actress Marie Bittnerová over Pospischil.

Šubert resented her diva-like attitude and demanded discipline and obedience. Pospischil defied the authority of the director, who was known, among other things, for demanding sexual favors from actresses in exchange for casting opportunities or a salary increase.[8] Whether Bittnerová was Šubert's lover is questionable, but not impossible[9] (her husband, actor Jiří Bittner, drafted the memoirs, which after his death Šubert collected from his literary estate and destroyed). Since scandals of this kind rarely appeared in the media of that day, Prague theatre circles were amused by the information, true or fake, about Pospischil slapping Šubert.

Bittnerová was also said to be self-centered and ambitious as Pospischil, and she vilified her younger colleagues, left the troupe twice when her expectations had not been met, and Šubert excused her exclusive demands: "Mrs. Bittner was given the opportunity by the National Theater to achieve great artistic goals, but it was not possible to satisfy her claim that she would be the only one for all the first roles as she expected."[10]

In the winter of 1884, Pospischil had fierce disputes with the director over his casting decisions in the highly expected new French melodrama, Ohnet's The Ironmaster. Šubert assigned the role of Claire, the female lead to Bittnerová. Pospischil, who also wanted the role of Claire, refused to submit to him any longer and published her critical opinion on conditions at the theatre: "The systematic killing of my talent and my health by the director of the National Theatre, Mr. František Šubert, pushed me to resign immediately. I will explain the details of the behind-the-scenes intrigues and love affairs of which I am the victim to my beloved audience later, when I am of a cooler mind. God knows I hate to say goodbye to an audience that has always treated me so kindly and dearly, and I assure here on my honor that I would serve this national institution until my last breath if it were led by a man who values the sacred purpose of the National Theatre more highly than his appetites." This quote was both published in newspapers and handed out in the National Theatre on the day of Bittnerová's performance. Pospischil, who refused to submit to Šubert's demands, was the first and only one to speak publicly about Šubert's sexual relationships with actresses. Some newspapers hinted at his sexual misconduct, e.g. that "theatre directors are trying their luck in love, but they hit Miss Pospíšil's heart hard."[11] Several newspapers mentioned "mysterious incidents behind the curtain making the return of previously very obedient and respected Pospischil hardly possible."[12] Most of the newspapers were silent about the incident. Some accused Pospischil of a calculated move, having planned to start a career on the German stage and looking for an excuse.[13] Most newspaper articles passed over the reasons for her departure and the protest in silence.

Both, she and Pulda, were dismissed. They tried to reconcile with Šubert, but in vain. Šubert did not accept their apology and he never forgave Pospischil for her media insult.[7]: 67 A number of Czech politicians tried to soften the director's harshness and lobbied for Pospischil, but in vain as well.[4] Pospischil, although later she was repeatedly asked about the reasons for her actions and choice of words, never commented on this topic.

Discussions about her possible return were going on for more than ten years. In 1890, for example, František Ladislav Rieger said: "Miss Pospischil left the National Theatre in a disgraceful way that can never be forgiven."[14] Later, however, he reduced his sentence and left the decision on her return to the management of the theatre.

Polish tour and Prague German Theatre[edit]

After being dismissed, Pospischil appeared as a guest star on Polish stages from January to May 1885. Unemployed actress took the opportunity (most likely suggested by writer and journalist František Hovorka, who was well acquainted with Polish culture life).

Pospischil performed in Czech, which was found a nice gesture of Pan-Slavism and easy to understand due to the proximity of both languages. Her repertoire was very wide and she performed a number of new roles in Poland, probably boosted by her very enthusiastic reception. Her Polish audience couldn't fully understand her, so she was forced to focus on the physical means of acting (voice work, gestures and body work).

She toured Warsaw, Poznań, Lublin and Kraków and presented Gretchen in Goethe's Faust and Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro from her older repertoire, but the status of a freelance artist gave her the opportunity to choose her own Rollenfach and roles. She started to work on her French repertoire and played Marcelina de Targy in Octave Feuillet's Parisian Romance, Ciprienne in Divorçons by Victorien Sardou and Émile de Najac, Frou-Frou by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy or Victorien Sardou's Fédora.[15] These were popular show-off roles - a part of the regular repertoire of all the most outstanding actresses of salon comedies in Europe. Usually impressive, but also dangerous because it gave opportunities for comparison. And Polish audicence was aware of work of Sarah Bernhard and the famous countrywoman Helena Modjeska. To honor the Polish hosts, she also staged the comedy Fat Fish (Grube ryby) by Michał Bałucki.

Her success was all the more astonishing because she played many of these roles for the first time. In addition, the acquisition of more than a dozen expensive period costumes, including several months without work, required a large financial and time investment that she (and Pulda) could afford.

She was an enormous success and was received very favorably and even enthusiastically. Not only a great artist was welcomed, but also a "representative of her fellow nation", as Ludwik Kozłowski stated in his review: "It was a true manifestation of cordiality: – Miss Pospiszilówna, when she first appeared on the stage, was greeted by a veritable hurricane of applause and thousands of shouts: "Na zdar! Cheers!... Long live the Czechs!..."[16] The orchestra wrapped up the performance playing the Czech national song Kde domov můj. It was not just the panslav feelings in the audience. The Polish audiences were truly amazed by Pospischil. In the same review, Kozłowski concluded: "However, we can rightly conclude that such a cordial reception of the artist and passionate celebrations of her and our brother nation was bestowed upon its worthy representative."

She could move audience to tears. But some critics also mentioned "spots in the sun" in her acting style, that were to be overcome later in Vienna, "excessive facial expressions that tire the audience's attention, overuse of dramatic tones in places requiring calmer diction, and movements - sometimes too violent - for a set of a parlour (of a French comedy Divorçons). The artist's playing lacks peace and concentration.[17]

In Kraków candies called "Sleczna Pospiszilówna" (Miss Pospischil) appeared in the confectionery shop of Mr. Hendrich and Rehman.

At that time, the National Theatre was the only Czech theatre in the territory of Bohemia. All other theatre companies did not have a permanent building and traveled around Czech-speaking regions, or they were German theatre houses in the German-speaking regions of Bohemia. She, not willing to be a touring actress, was forced to pursue a career on the German stage. Her first performance in German took place at the Prague German theatre in the summer of 1895, being invited by director Angelo Neumann. She starred in Schiller's The Maid of Orleans.[18]: 91 Pospischil did not speak German well (which was rather unusual, as most Czech actors were bilingual at that time) and had to memorize all the German roles phonetically. Later in her career she became fluent in German and minimized her Czech accent.

After her Polish tour, where, next to the role of Gretchen in Faust, she mainly performed French salon repertoire, Pospischil started with a new set of roles, this time German classics in the original version.

Other roles she performed in German in Prague, also by Schiller, were Princess Eboli in Don Carlos and the title role of Maria Stuart. She continued to play these roles throughout her career, both in Vienna and Berlin. Her first German success must undoubtedly be credited to her tutor Pulda, as the certainly undeniably talented actress did not have enough experience to portray new leading roles in a foreign language she did not fully master.

Her Prague German appearances caused very negative reactions and feelings in Czech patriotic circles, because it was customary for Czech actresses to play only in Czech in the territory of Bohemia. If they played in German, it was outside the territory of the Bohemian Kingdom. The worst attack came from the Czech journalist Emanuel Bozděch, who partly made a living by writing for Prague's German newspapers. In a German-written feuilleton he questioned the choice of Pospischil for this great Schiller figure - because she - as was a common knowledge - was neither German nor a virgin.[19]

Berlin and Vienna[edit]

-

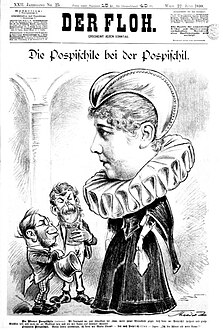

Maria Pospischil riding the Bohemian Lion to Burgtheater on the front page of Die Bombe magazine in June 1890

-

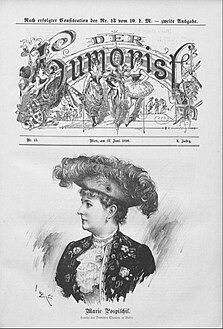

Maria Pospischil in Der Humorist

-

Agatha Bârsescu and Maria Pospischil fighting while Charlotte Wolter calmly watching

-

1892 new year's issue of Der Humorist, artistic trio of the Burgtheater: Charlotte Wolter (top), Maria Pospischil and Katharina Schratt

Pospischil's performance in Prague's German Theatre attracted the attention of many German theatre agents and directors. Artistic leader of the Deutsches Theater in Berlin Adolphe L'Arronge invited her for guest performances of Princess Eboli in Don Carlos and the title role of Donna Diana by Agustín Moreto y Cavana. She became a member in the character type of tragic heroine from 1887 to 1890. She was praised for her portrayals of the characters of Adelheid von Walldorf in Goethe's Götz von Berlichingen, Lady Milford in Schiller's Intrigue and Love, Maria Stuart, Franz Grillparzer's Sappho, Salomon Hermann Mosenthal's Deborah or Hjördis in Henrik Ibsen's The Vikings at Helgeland. After her portrayal of Empress Messalina in Adolf Wilbrandt's Arria and Messalina (a role originated by the Burgtheater star Charlotte Wolter) she was called the "North German Wolter. When compared to her: "Maria Pospischil played the role of Messalina, and what Mrs Wolter owed her, she embodied in an almost ideal way. Wolter didn't represent Venus, the woman into whose arms the intoxicated Marcus stumbles like a blinded moth into the scorching light was missing. In Miss Pospischil's portrayal, the love scenes in particular gained an irresistible magic. The way she, gracefully cast on the colorful leopard skin, sweetly lured the dreamy youth to her, the way she rested wreathed with roses on the snowy cushions of the Venus temple…"[20]

In 1889, she was invited to Vienna by the director of Burgtheater August Förster in an effort to find a replacement for the aging Charlotte Wolter, one of the greatest German tragic heroines, a generation older actress of the same repertoire and a darling of the Viennese audience.

After guest star presenting Countess Orsina in Gotthold Ephraim Lessing's Emilia Galotti, Maria Stuart and Countess Udaschkina in Graf Waldemar by Gustav Freytag director Burckhard (who became the director after Förster's sudden death) hired her as a replacement for the Romanian tragedian Agatha Bârsescu who she complained that she didn't get enough role opportunities and decided to pursue her career in Hamburg. Although her contract at the time still tied her to the Deutsches Theater for two years, Burthardt managed to release Pospischil from her old obligations by paying a considerable penalty. Pospischil became a court actress and for that reason she turned down an attractive offer to perform in America.[21]

Pospischil was expected with high anticipation and approved even by Wolter's admirers: "If Pospischil is smart, she'll learn from Wolter what she can. The rest is in good God's hands. We can be modest and considerate and you drink lemonade gazeuse if we don't have champagne."[22] She debuted as Princess Eboli. The risqué décolletage of her costume became the talking point of her first performance.[23] She also performed William Shakespeare's Juliet, Goneril and Brutus' wife Portia. She starred in many other roles, such as, Ibsen's Magrit in The Feast at Solhaug and Sigrid in The Pretenders, and Queen Kunigunde von Massovien in König Ottokars Glück und Ende, the title roles in Donna Diana by Moreto and Dumas' Denise, Delphine de Girardin's Lady Tartuffe, or Duchess of Marlborough in The Glass of Water by Eugène Scribe. She originated the roles of Victorien Sardou's Fédora (showcase role of Sarah Bernhardt) or Clotilde, Princess de Charges in Octave Feuillet's The Divorce of Juliette.

She became a socialite in Vienna and often appeared in society, famous for her lavish gowns designed according to Paris fashion (Pospischil took trips to Paris for inspiration, and some of her outfits might have been purchased in Paris). During that period Pospischil performed for German audiences in Czech and Moravian cities, Pilsen, Olomouc and Brno, and Czech patriots later reproached her for that.

Fight with Wolter[edit]

Same as her predecessor Bârsescu, she remained overshadowed by one of the greatest German tragic heroines Charlotte Wolter, she eventually gave up the fight with Wolter. "Young" Pospischil got more opportunities only when "old" Wolter was indisposed and sick[24] and the young ambitious actress felt that her potential was not being fully utilized. The conflict between the two divas became a subject of a discussion about the future and direction of the Burgtheater.[25]

In early 1891 a “Wolter-crisis” (Wolter-Krise) broke out Wolter declared that she would resign from the Burgtheater because of "insults from the management"[26] which she could no longer tolerate - i.e. Pospilchil taking over some of the roles previously played by Wolter. Satirical magazines considered her demands excessive and ridiculed her for another fifty years at the Burgtheater.[27] Wolter also expressed disapproval of Pospischil as her successor and suggested other actresses instead of Pospischil, esp. Adele Sandrock, a tragic heroine in Volkstheater (Sandrock was eventually artistically more significant, and also more progressive. She actually joined the Burgtheater in 1895, but left due to disagreements with the management in 1898).[28]

In February 1892, Pospischil became inpatient because she didn't get many performance dates and openly complained about the lack of employment to director Burckhard. Her complaint was justified, because in the first two months of 1892 she only performed at the Burgtheater only three times as Queen Kunigunde in Grillparzer’s König Ottokars Glück und Ende, Sigrid in Ibsen’s The Pretenders and finally Princess Eboli in Schiller’s Don Carlos (she was touring in German-Bohemian spa Teplice). Wolter appeared in all the major roles (e.g. Schiller’s Maria Stuart, Shakespeare’s Hermione, Wilbrandt’s Messalina or Grillparzer’s Sappho, and appeared on stage four times more often.

Pospischil was also overshadowed by the young tragedian Adele Sandrock, a star of the Deutsches Volkstheater who, however, played modern heroines in addition to the classical repertoire.

A new feud with Wolter began when the Burgtheater management decided to cast 58-year old Wolter in a role of a 26-year old tragic heroine (and her young romantic partner played by 65-year old Bernhard Baumeister[29]) in a newly produced drama Kriemhild by Wilhelm Meyer. Wolter had the right to keep the roles she had already studied (which was most of the classical repertoire). She made herself clear that she would not give up any role to Pospischil when she reached the age of one hundred.[30] But she did not have the exclusive right to be cast in new plays. Director Burckhard, however, could not or did not want to deal with the aging diva and cast her as the young romantic lead. At the same time, he started Sunday afternoon discounted shows for workers, and there was a rumor that, in addition to his social sensibilities, he needed to find dates for a young tragedian. “The management of the Imperial and Royal Hofburg Theater, as well as the great actress Charlotte Wolter, who, however, thinks and acts very pettily in "certain" things, is doing everything in their power to spoil the position of this talented and important artist at the Burgtheater. Mrs. Wolter likes to try to "play" Miss Pospischil out of the theater in a similar way she once successfully managed to get rid of Miss Katharina Frank. However, we believe that this time, despite the strong support of the director Dr. Burckhard, she will not succeed, and we are certain that Miss Pospischil is sensible enough to calmly defy all hostility and intrigue, for at that time Mrs. Wolter was 18 years younger, whereas today, even if she herself does not believe it, she has already become a matron.”[31]

Even her friendship with the influential actress Schratt did not help her break through. "Miss Pospischil, who was unable to establish herself either in the repertoire or with the public, leaves Vienna."[32] Pospischil decided to go back to Berlin. The position of first tragedian was offered to Rosa Poppe and later Adele Sandrock but neither of them was able to keep the position either. Pospischil later regretted this decision, because Wolter's career was slowly coming to an end and Pospischil assumed she could have soon become the first tragic heroine of the Imperial theatre.[32]

It is important to note that Berliner and Viennese theatre critics originally mocked Pospischil for her "typical Czech overacting mannerisms" or "declamatory style and strove for natural truth in expression"[33] and she was successful in recreating her acting style. Her youth and grace were her great assets, as in the case of Adelheit von Walldorf in Götz von Berlichingen, that she played after Wolter: "Miss Pospischil is still young and beautiful; Her youth and beauty make us believe in many things that we must have forgotten about the tragic actress (Charlotte Wolter) of a certain age."[34] Her expensive costumes and jewels, esp. those in Fédora, became sensational.[35] She was often referred to as "Marianka" or "Mařenka"[36] which is a derogatory term of a Czech peasant girl, after Mařenka, the main role of Czech opera The Bartered Bride popular in Vienna at that time. The Viennese journalists and public opinion was that she was histrionic and had many breakdowns she had to recover from in Merano due to stress conditions in the Burgtheater. However, many Viennese regretted her departure because she was no longer there to replace the aging sixty one year old Charlotte Wolter, who had become too old to portray certain youthful roles, although her acting skills were still great.

Alongside Ludwig Barnay[edit]

In 1893, after her three-year contract expired, she left Vienna and returned to Berlin. She obtained an engagement in the Berliner Theater under the artistic guidance of Ludwig Barnay. Here she began to move from the roles of young naive lovers (such as Juliet or Louisa Miller) to the genre of mature tragic heroines (such as Lady Milfort in of Schiller's Intrigue and Love, Grillparzer's Sappho and Schiller's Maria Stuart). After her arrival she appeared in a.i. the double role of young widow Victorine von Meerheim and Italian Renaissance aristocrat Isotta degli Atti in Joseph Victor Widmann's Jenseits von Gut und Böse. She received high for her ability for portraying such unsympathetic roles as Meerheim and Isotta commendably. She also performed in Russia.

The German actor and director Ludwig Barnay was one of Pospischil's most frequent stage partners.[37] Pospischil performed with him as the lead in Desdemona, Lady Macbeth, Lady Anne, Goneril, or Madame Pompadour in the tragedy Narziss by Albert Emil Brachvogel. Her other roles included Magdalena von Hohenstraßen in Paul Lindau's Maria and Magdalena, the treacherous Countess Zicka in Victorien Sardou's Dora or Adolf Wilbrandt's empress Valeria Messalina. Here Pospischil's stagecraft reached its peak for the first time. These doomed characters often ended in a tragic death of the main heroine and required luxurious gowns and costumes, which at that time the actresses had to provide at their own expense, often causing them to seek rich patrons to sponsor them[38] as each role demanded another set of expensive costumes, often of various historical styles, ranging from Ancient Rome, the Renaissance and Rococo style to contemporary designs. Pospischil became famous for investing great sums of money in her lavish gowns and the newspapers often admired her fashion style and gained the status of a fashion icon in Berlin. This practice of lavish costuming was widely criticized as it distracted from the dramatic text and the performance of the actress. Bernhard Bauer quoted as saying that the poster should tell both the name of the actress and of her fashion designer.

Return to Prague and media outburst against Pospischil[edit]

-

Maria Pospischil

-

Maria Pospischil around 1895

-

Maria Pospischil in a hunting outfit by photographer Jan Mulač

-

Maria Pospischil as Adelheid in Götz von Berlichingen

-

Maria Pospischil

In the spring of 1895, Pospischil attempted to return to the Czech stage. Her personal motivation remains unclear. One of the reasons could be the death of her close friend and possible lover Antonín Pulda, who during one of his visits to Prague, died suddenly of a severe stroke. Also, Barnay resigned as director of the Berliner Theater. Playwright and theatre critic Oskar Blumenthal became the new director. However, after only one year, he left the artistic direction to Alois Prasch.She kept repeating that she would love to return to her beloved homeland (i.e. abandon her stellar German career). She was still remembered by her Prague fans. Part of the subscribers wanted her to return and even wrote a public petition as early as 1886 for the theater to strive for her return.

She was invited to Prague by the board of trustees of the National Theatre, namely head of the board Jan Růžička against the will of director František Šubert,[39] who repeatedly expressed his disapproval of her return. His arguments were that Pospischil performed in German theaters in Czech-German cities and thereby undermined Czech culture (especially in the German Theater in Prague). She also gravely insulted him in the press and did not publicly apologize to him. He presented her conciliatory attitude as calculation. He also predicted that her return would endanger the discipline of the ensemble, because the members would know that they could stand up to the director and after some time they would be forgiven and accepted back.[40]

It is possible that the board of trustees were using Pospischil to test the authoritative director and only were using her as a means of power struggles, which had been very tense between the director and the board for almost a year.[41]

Pospischil was willing to give up other lucrative European offers in order to perform at the National Theatre again and eventually to return to Prague but her efforts to reestablish a career in Bohemia were thwarted not only by Šubert's ongoing antipathy of her but also the ultra-radical national faction of Czech patriots, who did not want Czech actresses to pursue a career on the German-speaking stage.

Theatre critic Jaroslav Kvapil believed that the problem was Pospischil's cosmopolitan life attitude, which provoked resistance in the Czech environment: "The young lady does not hide her internationalism despite various journalistic statements, and her entire life so far is proof that the essence of our displeasure towards her actions she couldn't understand before."[42] Historian Milena Lenderová sums up: "If a Czech actress was driven to a German stage by intrigue or destitution, Czech public forgave her. However, she was not allowed to stand out too much there."[41]

Her return had very bad timing during a time of strong national turmoil between Bohemian Czechs and Germans. The Czech company was shortly after the Omladina Trial. Pospischil was chosen to be a warning example for other actors. She was called the "national Mary Magdalene".[43] The German media used the opportunity to point out Czech xenophobia and chauvinism:"What penance would be great enough to atone for all this guilt? Some are of the opinion that such a thing cannot be atoneed for at all. Only the purifying fire of a miracle is strong enough to eradicate these pro-German feelings deeply rooted under one's skin, but others are of the opinion that Miss Pospischil would be such an effective figure as a national Magdalene that even the most fanatical German-haters would have to forgive her."[44]

The subjects of her national treason were as follows: in the 1890 census, when she was living in Vienna, she stated that she was of German nationality. In Germany and Austria, she used the German spelling of her name instead of the Czech one (this was common practice at the time - even other Czechs e.g. František Šubert and Antonín Dvořák, were often spelled as German names - Franz "Schubert"[45] and Anton "Dvorzak"[46]). Nobody seemed to care that during her Polish tour in 1885 Polish newspapers had called her Marya Pospiszilówna.[15] Pospischil agreed to change the spelling, apparently wanting her name to be pronounced correctly rather than garbled.[47] The strongest moment of treason, which Pospischil was denying all her life, was her performance in favour of the German Schullverein, a German association to support German national education, especially against the growing nationalism of the Slavic peoples in imperial Austria.

Although Pospischil was not the first Czech actress who had returned to Prague after a successful German career (so had done e.g. Marie Bittnerová or Julie Šamberková before her but without such a striking triumph), but this time radical patriots saw in her comeback, as well as in her success in Berlin and Vienna and lavish gowns sponsored by German aristocrats, a mockery of their efforts for the language equality of Czechs with the German minority in Bohemia.[41] The actress made a public apology for her earlier improper behavior, explained her attitudes in an interview [48] with journalist and war correspondent Servác Heller and donated the salary for the first four Czech performances to charity, but this did not calm the nationalistic passions.[42]

In his magazine, Czech journalist Jan Herben wrote about her "Who deserts, shoot them" and criticized her violation of national discipline,[49] and lamented about the fact that Prague bourgeoisie was blinded by the splendor of her outfits: "It is a shame how both (the strongest Czech) political parties lay at the feet of a lady who has beautiful gowns."[50]

Pospischil was referred to her as the mistress of an unpopular Governor Franz, Prince of Thun and Hohenstein,[51] who was her big fan (and whose previous mistress, ballet dancer Enrichetta Grimaldi just left Prague). Thun was involved in supporting the actress. Šubert complained about him in a letter to the chairman of the board of trustees, that. "I was invited at the police headquarters, 1/ to write back to that lady that I forgive her 2/ to agree to her engagement."[52] Later, writer Viktor Dyk satirically described their liaison in his novel The Fingers of Habakkuk.[53]

She, however, did have many supporters, as the literary critic and journalist František Xaver Šalda[54] and novelist and dramatist Vilém Mrštík who dedicated her his first tragic drama Miss Urban to Pospischil.[55]

National Theatre riots[edit]

Her first public appearance in Prague in April 1895 as Russian princess Fédora in Victorien Sardou's tragedy of the same name was threatened by student demonstrations. The National Theatre was besieged by hundreds of rioters and the actress had to be escorted by police upon entering and leaving the theatre. Later when she appeared in front of the public on stage, hundred hired protesters rioted against her in the auditorium for eleven minutes. They shouted and whistled to prevent the actress from performing. This type of charivari was common in 19th century Central European culture. Likewise, riots during performances. However, this was an unusually large public shaming of women.

After the most aggressive rioters were arrested, Pospischil could begin her performance.[7]: 35 While in public opinion, the star was triumphing over the rioters, Pospischil announced backstage to the board members that she would complete her Bohemian tour and return to Germany. She did not want to be exposed to the risk of further displays of hatred.[56] The actress began negotiations with her Berlin agent. German and Austrian newspapers tried to capture the event objectively, but at the same time underlined the nationalist and misogynistic aspects of the affair.

Prague bourgeoisie was enthusiastic. They admired Pospischil's strength to resist the rioters, but also her expensive white fur coat as her performance was also Prague's biggest fashion show of that day. Four gowns in which she performed that evening were estimated at 7,000 guilders (roughly ten times her fee that evening) and it was speculated that they had been of Parisian provenance (they were actually designed in Viennese dressmaker Hermine Grünwald's fashion atelier).

In her diary, actress Hana Kvapilová captured Pospischil's behavior the following day. "A quick walk, indifferent greetings, nods of the head, short, terse questions, and grandiose casualness scared away all cordiality... There was nothing sweet or soft in her gaze. She looked coldly as if in ill-concealed anger. Maybe it just seemed that way." Before Pospischil's second performance, which again could have turned into riots, Kvapilová, as cold as Pospischil's behaviour, expected a more enthusiastic attitude from the star towards her performance at the National Theatre.[57]

Police supervised all performances. When violent riots became risky, the claque began to use positive boytot, such as calling to fame the national icon Otilie Sklenářová-Malá, who played the virtuous Aria alongside Pospischil as lustful Messalina. "During yesterday's performance of Miss Pospischil in Wilbrandt's Aria and Messalina, domestic tragedian Mrs. Sklenářová-Malá was enthusiastic applauded. (The ovation was mainly a demonstration of admiration for her strong nationalist attitude, the actress was known for her outdated stiff declamatory acting.) The standing ovations were continuously increasing as the evening progressed, and after Aria's big scene in the third act, they turned into outbursts of joyful demonstrations. Unfortunately, police got involved again yesterday, this time during loud applause in honor of Mrs. Sklenářová."[58] Unlike many other actors, Sklenářová-Malá tried to remain neutral in the conflict.

Subsequently, she performed at the National Theatre several more times, always with great success. She played in Frou-Frou, Queen Elizabeth of Pomerania in A Night at Karlstein and Beatrice in Much Ado About Nothing being her last Czech performance ever.

National Theatre contract[edit]

Pospischil first decided to go back to Germany after finishing the contracted performances, but during the tour, when the situation calmed down, she started negotiating a contract with Růžička. Šubert explicitly asked Růžička to be excluded from the contract negotiations. He was openly avoiding her and during the month she was performing, Šubert took a vacation and went to Italy.

Pospischil did not accept Růžička's contract draft and negotiated an unprecedented salary of 8000 Golden a year, which was more than twice the salary of the highest salaries of Jiří Bittner, the first tragedian of the troupe, or the highest paid actresses Benoniová and Laudová.[59] She became the first Czech actress with a higher contractual salary than an actor. She also specifically mentioned in the contract that the director would not have a final say in the decision on her role choice - she thereby completely excluded Šubert, as the director of the theatre, from influencing her career. This step, accepted by Růžička, would have destroyed Šubert's influence on the running of the theater without precedent. Šubert, in his published memoir, tried to achieve an objective view: "Losing Pospischil was, on the one hand, a loss for the theater, but given the conditions under which the artist was supposed to work and their consequences for the theater, it directly saved the theater: because the inevitable consequences of that ill-advised contract would have completely destroyed the situation inside the troupe in a few months. The effect of that contract on all other members of the theatre without distinction."[60] She signed a contract with the board of trustees of the National Theatre and entered into an engagement.

However, her ambition was thwarted after an unsuccessful personal meeting with director Šubert, who made it clear to her that he hated her presence in the National Theatre.[61] To this day, there is controversy about what happened between them on the meeting. Pospischil left indignant. She went directly to the chairman of the board of trustees, Dr. Růžička, and tore up the contract in anger. Letters from both Pospischil and Šubert, addressed to Růžička, are kept in the Prague literary archive and describe the whole affair in their points of view.

Pospischil, clearly trying to make peace with a man who had been harming her all along, felt insulted and lost her temper: "Mr. Šubert welcomed me as the last of the last employees of your theater. And to my explanation that I'd like to introduce myself as a new member of the theater appointed by you, he answered that he does not agree to any reconciliation. I was accepted against his will and that my contract protects me from his persecution and I imposed conditions to which he would never accede."[62]

Šubert, who contradicts himself in his description, was of the opinion that his behavior towards the actress was correct, however, he noted that the actress left saying: "My efforts at reconciliation were in vain."[62]

Šubert's motivation for his strong absurd resentment of Pospischil is hard to explain. According to many accounts, the director's personality did not get along with other prominent artistic personalities. The opera singer Bohumil Benoni, the husband of the actress Hana Benoniová, who also had a love affair with Šubert,[8] was strongly prejudiced against the director in his memoirs, but he briefly characterized Šubert's artistic management of the troupe, this "Šubert system" as follows: "Šubert was against any Star-system in the National Theatre. Therefore, as soon as someone became a star in the National Theatre, they had to either go abroad or voluntarily compromise their demands. The system mainly consisted of not allowing the artist's ego to grow too high. Therefore, once someone excelled in a great role, they could be sure that they would immediately be removed to some secondary role or cast against their type."[63]

František Xaver Šalda, the most famous Czech literary critic of his time, considered Pospischil to be one of the greatest Czech actresses, if not the greatest: "In Frou-Frou, Miss Pospischil represents an excellent will and passion, strong moral and physical figures, a sparkling foam of whimsy and boredom. The strong air of naturalism she exudes in many of the knife-edge scenes where the words sizzle around your lips like saliva is as healthy and fertile for the auditorium as it is for the stage. … So her Magda in Heimat has made the most profound impression on me, the most profound one I have ever got in theatre so far. The piece opened up and deepened with sincerity and inner experience, with that painful, broken, agitated fabric of life."[64] For Šalda and many others, her return to Germany in 1895 was an irreplaceable artistic loss[65] for the Czech theatre, and they blamed Šubert, who made Pospischil's return impossible due to his inplacability.

Jaroslav Kvapil evaluated her acting in the opposite way: "No genius, no creative power, no struggle with an ideal - nothing."[66] Thirty years later, Kvapil abandoned in his memoirs his previous bitterness and cross judgements and wrote: Her capitulation should have been accepted. Later, Šubert was not able to find a suitable substitute for Pospischil's talent, that young and breathtaking, albeit defiant charm.[5]: 44 Pospischil expressed regret of the forced end of her career in Bohemia repeatedly.[18]: 104

Pospischil was not the only Czech talent who was rejected and condemned to a career abroad by director Šubert. In 1897, he did not recognize the talent of the young soprano Emmy Destinn, and rudely rejected her,[67] forcing to also start a new career in Germany.

Berlin and Hamburg[edit]

-

Maria Pospischil as Adelheit in Götz von Berlichingen in Hamburg

-

Maria Pospischil as Fedora

-

Maria Pospischil

-

Maria Pospischil

-

Maria Pospischil

After her unsuccessful attempt to return to Bohemia, Pospischil decided to return to Germany and opened the season with a controversial role of wild and passionate Amazon queen Heinrich von Kleist's Penthesilea as well as in her showcase roles of Schiller's Maria Stuart and Goethe's Adelheid von Waldorf.[68]

In 1895 she stated in an interview: "I don't want to get married because I have absolutely no intention of giving up my art, to which I am passionately attached, and because I firmly believe that art is not compatible with marriage.",.[69] However, this does not necessarily mean that these are the actress' real opinions. She only might have presented herself publicly in that way in order to have wider opportunities for engagement in the contemporary context. "A large number of actresses' contracts have stated that marriage is an immediate reason for termination. … This basically means that at least the smaller stages take into account the sexual attractiveness of their actresses, and that the sexual interest of the men's world is weakened if the actress in question does not necessarily appear to be "free" but is officially claimed by a marriage alliance."[70]

She became a favorite actress of playwright Paul Lindau and created several of his plays, major hits at that time, e.g. operetta singer Nelly Sand in Die Brüder and Elise Maineck in Die Erste.

She also traveled to Dresden in 1897 for guest performances at the Dresden court theater, but the tour didn't result in a contract. She played in Meiningen Court Theatre. The same year, she toured Russia performing in the Alexandrinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg on invitation of director Philipp Bock.

In 1897 she married retired Prussian major Georg von Hirschberg and they had a daughter and a son.[18]: 91 Later, she often used Maria von Hirschberg as her stage name.

She was already such a well-known and notorious celebrity artist around Europe that a number of German and British newspapers printed her answer from a German theater enquiry: "When is a woman old?" - Mary Pospischil declares that "as long as a woman believes in youth and clings to her youth she appears young even when she is not really so."[71] She was known in Great Britain as the "divine Sarah from Bohemia".[72]

Her further artistic career was connected to the city theatre in Hamburg with a contract "under brilliant conditions"[73] where she began acting in 1898 in heroines and first tragic lovers (Rollenfach: Heroine und I. tragische Liebhaberin) . Here she gained the greatest fame and popularity with the audience. In particular, her portrayal of Lady Macbeth was celebrated as brilliant by many Hamburg newspapers.[74] She was pursuing her stage career until 1907, mainly in Hamburg.

In 1900, she made a guest tour in London, performing in German in St. George's Hall with great success and the newspapers referred to her as "an old favorite of London".[68]

In 1906, Pospischil opened her own theater company, Pospischil-Ensemble, and performed in Berlin as Fédora and Grillparzer’s Medea. She presented her first stage direction, Shakespeare's romance Cymbeline, a play rarely staged in Germany at that time (Pospischil only directed the production, she did not star in it; the main female lead was Julia Serda as Imogen). The company, though short-lived, was a considerable success.[75]

She stayed in Hamburg until 1907. She ended her engagement and moved back to Berlin. She decided not to enter any other engagement and turned down an offer of an American tour to start touring in German speaking countries. In 1908 she had a big tour around German cities, including Prague). She also gave a series of lectures on Johann Wolfgang Goethe and Goethe’s Faust in Berlin in 1907. She taught acting and had several students. Ilka Grüning became a prominent film actress, Alice Arnauld de la Perière became a tragedian, or also forgotten Martha Schneider, an actress in Rostock.

Later career[edit]

Between 1909 and 1913 she was the first director of the German theatre in Ústí nad Labem in German-speaking part of Bohemia. The grand opening of the opening theater became a spectacular cultural event in 1909. Pospischil reprised the title role of Franz Grillparzer's Sappho and later guest starred in local theatres (Magda in Teplice, Duchess of Marlborough in Litoměřice etc.) in her glamour roles. Pospischil used her earlier theatrical contacts to invite a number of guests, especially opera singers. “She ran the theater with honest artistic endeavors and one should have been satisfied with her; the undue and unjust demands of her members led to a conflict in which she finally fell victim to the "organization."”.[76] Among the most significant cultural acts is her commitment to the installation of a commemorative plaque to Richard Wagner in the ruins of nearby Střekov Castle, which had inspired the composer when writing his opera Tannhäuser.

Her era was an artiscic success but the theater had financial difficulties and Pospischil's husband, a military officer, managed the theater together with her and 21 artists left in the first season and another 18 in the following season (actors, opera singers and orchestra players) because of his arrogance.[77] Her management was described as conflict-ridden “belligerent”. Artists complained about strict military conditions (all communication had to be in writing, management did not accept personal meetings). Several artists filed complaints to the court for harassment and disregard for personal freedoms.[78] However, in the trial after hearing the witnesses Pospischil was acquitted of all charges.[79]

After she left Ústí nad Labem, she returned to Berlin and performed in the Theater in der Königsgrätzer Straße in the charater type of classical mothers and older character roles (Rollenfach: klassische Mütter und ältere Charakterrollen). Critics and audiences began to consider Pospischil too old for the tragic Rollenfach and she abandoned this character type voluntarily. She was under 50, while other actresses (Sarah Bernhardt, Charlotte Wolter) kept the tragic repertoire until a much older age, despite agism-based critiques.

In 1918, she returned to her acting career appearing in three minor German silent film, for example Mitternacht or Der Dornenweg.

She was widowed in 1930 and lived her last years in Stuttgart.

In 1943, she suffered a heart attack on the train on her way to the Bad Wiessee spa in Bavaria. She subsequently died in a nearby hospital in Tegernsee. Her remains were cremated in Munich and transferred to Berlin.[18]: 91

Pospischil's writing[edit]

Pospischil was also active as a writer. She frequently answered German theatre newspaper inquires. In 1895 she answered the Kussproblem enquiry - debate about how real a kiss should be on stage: "Since I am for truth and nature on the stage, I am in full favor of the fact that an actress should allow herself to be kissed and kiss her stage partner if her action requires it. Sometimes the effect of the whole scene depends on an actual real kiss."[80] In her time, such an attitude, not uncommon among actresses, still could be risqué. Many reputable theatres in Great Britain still banned actual kissing, and acting manuals had to explain how to simulate it.[81] She published a memory of her stage mother - a tribute to forgotten touring actresses - both in German and Czech.

She is known for her article Die Schamhaftigkeit auf der Bühne, in which she fiercely criticized the emerging expressionist movement: "The story of John the Baptist, as told in the Gospels, seems to have sufficient dramatic power and beauty to do without any additions or alterations. But modernity wants to invent the perverted whim of an immature girl who would cause disaster. Are the demands of these poets too great and the subject too complicated to be dramatized with honor, or are they speculating on the desire of the general public for spicy and strong drinks, for aphrodisiacs to whip up the weary nerves of our age? The obscenities of the French operetta of the 1860s, initially met with strong opposition in Germany, are now derided as harmless and have achieved record attendances. And even ten years ago, most of the works of Mr. Frank Wedekind's muse would certainly have been rejected by sensitive audiences and relegated to the realm of brothel cabarets." [82] and modern roles like Oscar Wilde's Salome.[83]

She was one of the first women Faustologists, i.e. writers who interpret Goethe's tragic play Faust in the book "Erläuterungen zu Goethes Faust, erster und zweiter Teil".[84]

Acting style[edit]

-

Maria Pospischil as Victorien Sardou's Fedora

-

Maria Pospischil

-

Maria Pospischil as Friedrich Schiller's Maria Stuart

-

Maria Pospischil as Franz Grillparzer's Sappho

-

Maria Pospischil as Eboli in Friedrich Schiller's Don Carlos

Pospischil was an interpreter of the classic roles of heroines in the grand style of the late 19th century. Both, her acting and lifestyle were to impress audiences in the theatre and on the street.[85] She was comparable to the greatest actresses of her time, Sarah Bernhardt, Eleonora Duse or Helena Modjeska. Playwright Paul Lindau admire described her character at the time with the following words: "Maria Pospischil is a heroine with the appearance of a salon lover and the voice of a sentimentalist, and her character is welded together by the passion of feeling."[33]

Most of her career, she had a stable position in an ensemble in the rank of tragic heroines and "Salondamen". But she toured Germany and many European countries. In her home stage, she often performed contemporary repertoire. For her touring career, she had a list of glamour roles (so called Glanz- und Paraderollen) of French (Fédora and Frou-Frou or La Dame aux Camélias) or German (Magda, Maria Stuart or Orsina) provenance. "Her brilliant roles include those in which a glowing sensuality is expressed, such as Messalina and Udaschkina in Freytag's Graf Waldemar."[86] These roles were risky because the audience got opportunity to compare the performance of various touring actresses: "She is one of the few actresses who does not let us think that the role has long been written. She fulfils Grillparzer's commandment to forget technique when doing art, frees the precious property entrusted to her from the dusty layer of routine and plays Maria Stuart as if it had been written for her and for her only. This freshness, which gives every speech and every part of the performance the charm of something new, a confident ability to shape to shape a character, conveys a truly extraordinary impression.[20]

Her natural beauty (dark brown eyes and thick golden-blond hair, so thick she didn't wear wigs) was her great asset. In her time she was considered one of the most beautiful Czech women. Especially roles of fallen women, "détraqués" (mentally unstable women), courtesans and wicked aristocrats brought her fame, as states a review of her rendition of Wilbrandt's Messalina: "In her portrayal, all sides of the character of the great courtesan were represented: the seductive grace of the hetaera, the demonic sensuality, the capricious mind, the insatiable thirst for revenge, the cunning of the upstart, but at the same time all the still shining through features of an originally great nature."[87] Or as Paul Lindau put it: "She was a Messalina of fiery sensuality, of blazing passion, full of hot longing in the first scenes, of melting devotion in the love scene with Marcus, of wild despair at Marcus's coffin, sinister in the bacchanalian frenzy of the final act."[87]

Voice was one of Pospischil's greatest assets, next to her sex-appeal. "Miss Pospischil is a heroine; she has mastered a character type. She brings physical means and a natural passion that many colleagues may envy; she is also modern enough to seek simplicity in her delivery, but as a heroine she believes she is obliged to offer a masterpiece of declamation at the right time. Mosenthal's operatic "Deborah" could only benefit from her performance. The author puts four great arias into the mouth of his heroine; Miss Pospischil made the impossible possible and spoke the gruesome curse with serious, strong effect."[88]

Pospischil was known for her frenetic activity on stage. Some critics condemned her for her restless running around the stage, and in her early years for overacting and convulsive facial expressions. Her rivals accused her of superficiality, but she thought about the interpretation of roles, about using vocal means, screams and emotional breakdowns: "With wise economy and artistic calculation on this key moment of Maria (Stuart), the actress emphasizes from the beginning of the role the woman broken by the shame of imprisonment and avoids all the heroic and energetic accents that are emphasized by most Stuart actresses, especially in the scene with Burleigh. Here the artist uses a more melancholy ironic tone."[20] Her Magda in Sudermann’s Heiman in 1894 got mixed reviews: “Miss Pospichil switches between brutal scorn and the softest sounds of emotion, but we can only believe there’s roughness in soft Magda, not that there’s softness in the rough one. Both are performed with equal virtuosity, but one seems to hear different instruments being played one after the other with the same skill: no harmony emerges. Miss Pospichil's ability is certainly significant, but after yesterday's performance she seems more of a virtuoso than an artist.“[89]

One of the trademarks of Pospischil's acting was the prolonged death scenes in the finale. Both critics[90] and spectators greatly appreciated how "she was dying very naturalistically - actually not pretty, but anyone who has witnessed a death will recall it watching her."[91] She was praised for dying in Frou-Frou in Prague, in Telesfor Szafranski's Das höchste Gesetz in Berlin or in Götz von Berlichingen in Hamburg. The Berlin review of Das höchste Gesetz stated: "The long, all too long dying is happening before our eyes. And Maria Pospischil dies with an art that gets to your heartstrings. You sit there and want to freeze in horror. I am convinced that many women who were at the theater didn't sleep a wink the entire following night. Maria Pospischil is admirably capable of great tragic tones. This death scene was full of "truth of life" and at the same time of the finest artistic stylization."[92] Another review of the same show revealed the impact of her naturalistic acting: "A terminally ill woman and wife who dies after a painful death struggle before the eyes of the audience. Marie Pospispil struggled with death in the Berliner Theater in such a nerve-shattering manner that the entire success of the play was called into question and in subsequent performances this brutal death scene was moved behind the scene."[93]

“Maria Pospischil was an actress of great style, but with too much style. Her mind and tongue were not quick enough to portray more complicated or, more correctly, more natural female characters.”[76] She was often criticized for her lack of tenderness. That's why, for example, she didn't impress in the role of Juliet, but she was praised in Lady Macbeth. Actress Hana Kvapilová, no friend of Pospischil, both admired and criticized her performance of Magda in Prague in 1895: "Magda was much warmer and even nicer, more likeable (than her Fedora). In the third act, nice shades of humour flashed through, but everything was rigidly determined, strong, sophisticated. The whole of her art, it seems to me, is a scale of effects of vocal, passionate, and maddened exclamations; her voice is strong like a bell, without vocal timbre, tenderness and womanly charm. … She must have trained herself with iron diligence and perseverance to become such a brilliant virtuoso. … Although meant to impress in the first place, she cries so naturally, she even uses a handkerchief that I believe she probably cries alone. But I didn't see tears in her eyes... She rages around the scene with two movements she constantly repeats: her hand in her hair (they say copying Duse) – and then she touches her ribs with both hands and slides her hands forward under her breasts. The whole performance is like a raging wind or perhaps the sea, noisy, sheer force and certainty." Kvapilová considered herself the opposite of Pospischil, but she was also older, tended to be fat, and had a weak voice that was not always understandable. Her husband, Jaroslav Kvapil, was equally critical and biting towards Pospischil. He wrote that the young lady wanted to be a world artist and she succeeded only on the route Berlin - Vienna and back: "All the triumph of the exterior, from the great toilets to the volcanic passion of the young lady, fascinated and conquered. The theater audience, which understands primarily only through the external sense organs, must have been captivated by these performances. She is the right actress for them, for all his perception, for all his hungry senses." And he further regretted that the young lady had to leave eleven years ago, but he considered the reason for her departure to be that "it is not in her nature to remain in one place."[42]

The acting style of the great tragic heroines - the one that Maria Pospischil mastered - went out of fashion during her lifetime. She preferred the classic repertoire of tragic roles, although she was often forced to appear in contemporary farces and social dramas, which she did not appreciate. Some critics, however, judged that, and on the contrary praised her performance as mother Dorothee in Mutterrecht by Adelheit Weber: "The actress, previously known only as a declaiming and posing iambic heroine, showed herself for the first time from a new, very remarkable side. She even almost succeeded in creating a real, living woman of flesh and blood on the stage from the literary material provided by the author - almost, but not quite!"[94]

As most of actresses of her rank (with the exception of Duse), she avoided contemporary progressive dramatic work (e.g. Ibsen's Nora or Hedda Gabler, or stage versions of Emile Zola's naturalistic novels). She was a significant Shakespearean actress of her time, creating the playwright's major female leads - Juliet, Desdemona, Lady Anne, Beatrice, Isabella von Valois, Portia in Julius Caesar, Goneril and Lady Macbeth, Among her greatest stage successes were great roles of German repertoire as Schiller's Lady Milford, Maria Stuart, princess Eboli in Don Carlos and Countess Terzsky, Goethe's Iphigenia and Adelheid von Walldorf, Grillparzer's Sappho and Adolf Wilbrandt's Valeria Messalina, or French dramas Fédora and Frou-Frou and Ibsen's Hjördis.[3] Sudermann’s Magda, a character of a woman who was forced to leave home and succeeded abroad, rarely staged Kleist's Penthesilea, woman who sees little difference between biting and kissing, and Schiller's penitent and doomed queen Maria Stuart bore a paradoxical resemblance to her life.

Roles played by Maria Pospischil[edit]

Roles performed in Czech[edit]

František Pokorný Theatre Company, Bohemian touring company

- 1878 - Strakonický dudák by Josef Kajetán Tyl - Dorotka

- 1878 - Faust by Johann Wolfgang Goethe - Gretchen

Provisional Theatre, Prague

- 1883 - Strakonický dudák by Josef Kajetán Tyl - Lesana

- 1883 - The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare - Nerissa

- 1885 - Intrigue and Love by Friedrich Schiller - Luise

- 1883 - Divorçons (Cyprienne) by Victorien Sardou and Émile de Najac - Cyprienne

- 1883 - Sulamit by Julius Zeyer - Lilith

National Theatre, Prague

- 1883 - A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare - Oberon

- 1883 - Much Ado for Nothing by William Shakespeare - Beatrice

- 1883 - Smiřičtí by Josef Jiří Kolár - Salomena Smiřická

- 1884 - Jedenácté přikázání by František Ferdinand Šamberk - Emma

- 1884 - A Night at Karlstein by Jaroslav Vrchlický - queen Elizabeth of Pomerania

- 1884 - The Marriage of Figaro by Pierre Beaumarchais - Suzanne

- 1884 - Marion de Lorme by Victor Hugo - Marion de Lorme

1884 Polish tour

- 1884 - Faust by Johann Wolfgang Goethe - Gretchen

- 1884 - Parisian Romance by Octave Feuillet - Marcelina de Targy

- 1884 - Divorçons by Victorien Sardou and Émile de Najac - Ciprienne

- 1884 - Fédora by Victorien Sardou - Fédora

- 1884 - Frou-Frou by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy - Gilberte (Frou-Frou)

Roles performed in German[edit]

Prague German Theatre

- 1885 - The Maid of Orleans by Friedrich Schiller - Joan of Arc

- 1885 - Maria Stuart by Friedrich Schiller - Maria Stuart

- 1885 - Don Carlos by Friedrich Schiller - Princess Eboli

- 1885 - Fédora by Victorien Sardou - Fédora

- 1885 - Die Carlsschüler by Heinrich Laube - Fraziska, Countess of Hohenheim

- 1885 - Donna Diana by Agustín Moreto y Cavana - Donna Diana

- 1885 - The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare - Portia

- 1885 - William Tell by Friedrich Schiller - Armgard

- 1885 - Fiesco by Friedrich Schiller - Julia, Countess and imperial dowager

Deutsches Theater. Berlin

- 1887 - Don Carlos by Friedrich Schiller - Princess Eboli

- 1887 - Donna Diana by Agustín Moreto y Cavana - Donna Diana

- 1887 - Emilia Galotti by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing - Countess Orsina

- 1887 - Götz von Berlichingen by Johann Wolfgang Goethe - Adelheit von Walldorf

- 1887 - Intrigue and Love by Friedrich Schiller - Lady Milfort

- 1887 - Arria und Messalina by Adolf Wilbrandt - Empress Valeria Messalina

- 1887 - Sappho by Franz Grillparzer - Sappho

- 1887 - Deborah by Salomon Hermann Mosenthal - Deborah

- 1888 - Richard III by William Shakespeare - Lady Anne

- 1888 - Macbeth by William Shakespeare - Lady Macbeth

- 1888 - The Ironmaster by Georges Ohnet - Athénais Moulinet

- 1889 - Eine Lüge von Emil Schönfeld - the fallen woman (die Gefallene)

- 1889 - Die Basallin by Albin Rheinisch - Countess Agnes von Boulogne

- 1890 - The Vikings at Helgeland (Nordische Heerfahrt) by Henrik Ibsen - Hjördis

Burgtheater, Vienna

- 1890 - Don Carlos by Friedrich Schiller - Princess Eboli

- 1890 - Maria Stuart by Friedrich Schiller - Maria Stuart

- 1890 - Graf Waldemar by Gustav Freytag - Countess Udaschkina

- 1890 - Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare - Juliet

- 1890 - Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare- Portia

- 1890 - King Lear by William Shakespeare - Goneril

- 1890 - Emilia Galotti by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing - Countess Orsina

- 1891 - The Pretenders by Henrik Ibsen - Sigrit

- 1891 - The Feast at Solhaug by Henrik Ibsen - Magrit

- 1891 - Ein treuer Diener seines Herrn by Franz Grillparzer - Queen Gertrude

- 1891 - Graf von Esser oder die Gunst der Fürsten by Banks, Brook, Jones and Ralph - Countess Ruthland

- 1891 - König Ottokars Glück und Ende by Franz Grillparzer - Queen Kunigunde von Massovien

- 1892 - Donna Diana by Agustín Moreto y Cavana - Donna Diana

- 1892 - Les pattes de mouche (Der letzte Brief) by Victorien Sardou - Suzanne

- 1892 - Richard III by William Shakespeare - Lady Anne

- 1892 - Denise by Alexandre Dumas fils - Denise

- 1892 - Lady Tartuffe by Delphine de Girardin - Lady Tartuffe

- 1892 - The Glass of Water by Eugène Scribe - Duchess of Marlborough

- 1892 - Richard II by William Shakespeare - Isabella of Valois

- 1892 - Fédora by Victorien Sardou - Fédora

- 1892 - The Divorce of Juliette by Octave Feuillet - Clotilde, Princess de Charges

- 1892 - Deborah by Salomon Hermann Mosenthal - Deborah

- 1892 - William Tell by Friedrich Schiller - Armgard

- 1892 - Arria und Messalina by Adolf Wilbrandt - Empress Valeria Messalina

- 1893 - Bernhard Lenz by Adolf Wilbrandt - Sarah Roland

1891 Prague tour (Prague German Theatre)

- 1891 - Fédora by Victorien Sardou - Fédora

- 1891 - Arria und Messalina by Adolf Wilbrandt - Empress Valeria Messalina

- 1891 - Maria Stuart by Friedrich Schiller - Maria Stuart

- 1891 - Emilia Galotti by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing - Countess Orsina

Berliner Theater, Berlin

- 1893 - Jenseits von Gut und Böse by Joseph Victor Widmann - Victorine von Meerheim / Isotta degli Atti

- 1893 - Die guten Freunde (Nos Intimes) by Victorien Sardou - Madame Caussade

- 1894 - Othello by William Shakespeare - Desdemona

- 1894 - Macbeth by William Shakespeare - Lady Macbeth

- 1894 - King Lear by William Shakespeare - Goneril

- 1894 - Maria and Magdalena by Paul Lindau - Magdalena von Hohenstraßen

- 1894 - Richard III by William Shakespeare - Lady Anne

- 1894 - Narziss by Albert Emil Brachvogel - Madame Pompadour

- 1894 - Dora by Victorien Sardou - Countess Zicka

- 1894 - Arria und Messalina by Adolf Wilbrandt - Empress Valeria Messalina

- 1894 - Graf Waldemar by Gustav Freytag - Countess Udaschkina

- 1894 - Heimat by Hermann Sudermann - Magda

- 1894 - Frou-Frou by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy - Gilberte (Frou-Frou)

Roles performed in Czech[edit]

National Theatre, Prague (tour)

- 1895 - Fédora by Victorien Sardou - Fédora

- 1895 - Heimat by Hermann Sudermann - Magda

- 1895 - Arria und Messalina by Adolf Wilbrandt - Empress Valeria Messalina

- 1895 - Frou-Frou by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy - Gilberte (Frou-Frou)

- 1895 - A Night at Karlstein by Jaroslav Vrchlický - queen Elizabeth of Pomerania

- 1895 - Much Ado for Nothing by William Shakespeare - Beatrice

Roles performed in German[edit]

Berliner Theater, Berlin

- 1895 - Penthesilea by Heinrich von Kleist - Penthesilea

- 1895 - Heimat by Hermann Sudermann - Magda

- 1895 - Maria Stuart by Friedrich Schiller - Maria Stuart

- 1896 - Renaissance by Franz Koppel-Ellfeld and Franz von Schönthan - Marchesa Gennara

- 1896 - Fédora by Victorien Sardou - Fédora

- 1896 - Intrigue and Love by Friedrich Schiller - Lady Milfort

- 1896 - Heinrich und Heinrichs Geschlecht by Ernst Wildenbruch - Queen

- 1896 - William Tell by Friedrich Schiller - Armgard

- 1896 - Kaiser Heinrich by Ernst von Wildenbruch - Empress Praxedis

- 1896 - Der Probenfeil by Oscar Blumenthal - Hortense

- 1897 - The Maid of Orleans by Friedrich Schiller - Joan of Arc

- 1897 - Mutterrechte by Adelheit Weber - Dorothee

- 1897 - Die Weisheit der Aspasia by M. Löbel - Aspasia

- 1897 - Die Brüder by Paul Lindau - Nelly Sand

- 1897 - Deborah by Salomon Hermann Mosenthal - Deborah

- 1897 - Faust, Part Two by Johann Wolfgang Goethe - Helena

- 1897 - Das höchste Gesetz by Telesfor Schafranski - Marie Treder

Meiningen Court Theatre

- 1895 - The Feast at Solhaug by Henrik Ibsen - Magrit

- 1896 - Der König by Richard Boß - Maurin Mira

- 1896 - Die Erste by Paul Lindau - Elise Maineck

Dresden Court Theatre

- 1896 - Theodore by Victorien Sardou - Theodore

- 1896 - Maria Stuart by Friedrich Schiller - Maria Stuart

- 1896 - Fédora by Victorien Sardou - Fédora

- 1896 - Sappho by Franz Grillparzer - Sappho

- 1897 - Götz von Berlichingen by Johann Wolfgang Goethe - Adelheit von Walldorf

1896 Saint Petersburg tour (Alexandrinsky Theatre)

- 1896 - Heimat by Hermann Sudermann - Magda

- 1896 - Renaissance by Franz Koppel-Ellfeld and Franz von Schönthan - Marchesa Gennara

- 1896 - Sohn des Khalifen by Ludwig Fulda - Morgiana

Hamburg City Theatre

- 1898 - Alarich, König der Westgoten by Julius von Verdy du Vernois - Severa

- 1898 - Maria Stuart by Friedrich Schiller - Maria Stuart

- 1898 - Don Carlos by Friedrich Schiller - Princess Eboli

- 1898 - The Maid of Orleans by Friedrich Schiller - Joan of Arc

- 1898 - Fédora by Victorien Sardou - Fédora

- 1898 - Drayman Henschel (Fuhrmann Henschel) by Gerhart Hauptmann - Malchen Henschel

- 1898 - La muette de Portici by Daniel Auber (opera), with a libretto by Germain Delavigne, revised by Eugène Scribe - Fenella (silent role)

- 1898 - Iphigenia in Tauri by Johann Wolfgang Goethe - Iphigenia

- 1898 - Medea by Franz Grillparzer - Medea

- 1898 - Judith by Friedrich Hebel - Judith

- 1898 - Wallenstein by Friedrich Schiller - Countess Terzky

- 1898 - Das Goldene Flies by Franz Grillparzer - Medea

- 1899 - Sappho by Franz Grillparzer - Sappho

- 1899 - Fiesco by Friedrich Schiller - Countess Julia

- 1899 - Die beiden Leonoren by Paul Lindau - Leonore

- 1899 - Intrigue and Love by Friedrich Schiller - Lady Milfort

- 1899 - Herostrat by Ludwig Fulda - Klytia

- 1899 - Die Journalisten by Gustav Freytag - Adelheid

- 1899 - Das Recht auf sich selbst by Friedrich von Wrede - Anina

- 1899 - Gewitternacht by Ernst von Wildenbruch - Maria Josepha

- 1899 - Frou-Frou by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy - Gilberte (Frou-Frou)

- 1899 - Die Erste by Paul Lindau - Elise Maineck

- 1899 - Heimat by Hermann Sudermann - Magda

- 1899 - The Merchant of Venice by William Shakespeare - Portia

- 1900 - The Vikings at Helgeland (Nordische Heerfahrt) by Henrik Ibsen - Hjördis

- 1901 - Ahasver in Rom by Robert Hamerling/Julius Horst - Empress Agrippina the Younger

- 1902 - Emilia Galotti by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing - Countess Orsina

- 1902 - Gyges und sein Ring by Friedrich Hebbel - Rhodope

- 1906 - When We Dead Awaken by Henrik Ibsen - Irene, the traveling lady

- 1907 - Lady Windermere's Fan by Oscar Wilde - Mrs Erlynne

1900 London tour (St. Georges Hall)

- 1900 - Sappho by Franz Grillparzer - Sappho

- 1900 - Iphigenia in Tauris by Johann Wolfgang Goethe - Iphigenia

1908 Prague tour (Prague German Theatre)

- 1908 - Fédora by Victorien Sardou - Fédora

- 1908 - Die andere Gefahr (L'Autre danger) by Maurice Donnay - Claire Jadain

- 1908 - Die Erste by Paul Lindau - Elise Maineck

Berlin, Theater in der Königgrätzer Straße

- 1913 - Brand by Henrik Ibsen - Brand’s mother

- 1913 - Richard III by William Shakespeare - Queen Margaret

- 1913 - Die Kronbraut (Kronbruden) by August Strindberg - Kersti’s mother

- 1914 - Die Trenkwalder by Karl Schönherr - Die Patscheiderin

- 1914 - Macboulé (Macbouleh) by Marie von Hobe - Sultan’s wife (Sultanin)

Schiller-Theater, Berlin, guest star

- 1917 - Die rote Zarin by Adolf Abter - Catharine the Great

Notes[edit]

- ^ Known by her Czech stage name Marie Pospíšilová and Maria Pospischil (also sometimes spelled Pospischill) or Maria von Hirschberg in Austria, Germany and Great Britain.

References[edit]

- ^ Olga Spalová, Sága rodu Budilova, p. 188.

- ^ František Pokorný, Vzpomínky a upomínky. p. 111.

- ^ a b Eva Šormová a.i., Česká činohra 19. a začátku 20. století: Osobnosti; , II. Part: N-Ž. p. 765.

- ^ a b Václav Štech, Džungle literární a divadelní. p. 35.

- ^ a b Kvapil, Jaroslav (1932). O čem vím: sto kapitol o lidech a dějích z mého života [What I Know: a hundred chapters about people and events from my life] (in Czech). Praha, Česko: Orbis.

- ^ Paul Schlenther, Der Frauenberuf im Theater. p. 53.

- ^ a b c Konečná, Hana (1984). Čtení o Národním divadle: útržky dějin a osudů [Reading about the National Theatre: scraps of history and destinies] (in Czech). Prague: Odeon.

- ^ a b Anna Lauermannová-Mikschová, Diaries. Literary heritage in the archive of Památník národního písemnictví.

- ^ Bohumil Benoni, Nová kniha vzpomínek a dojmů II. p. 57.

- ^ Ladislav Novák, Stará garda Národního divadla. P. 21

- ^ Besídka In. Paleček. Sešit 1, p.22.

- ^ Josef Kuffner Rozhledy. In. Květy. No 2, p.22.

- ^ Plzeňské listy. Jan 10 1895, p. 1.

- ^ Družstvo Národního divadla v Praze In. Čech. Oct. 20 1890 p. 3.

- ^ a b Jan Michalik, Marie Pospíšilová w Krakowie. In. Wielogłos. 2007/1 P. 85.

- ^ Ludwik Kozłowski, Drugi występ panny Pospiszilówny. In. Czas. 1885 P. 104.

- ^ Theatre review in, Drugi gościnny występ p. Marji Pospiszilównej. In. Gazeta Lubelska. 1885/77.

- ^ a b c d Novák, Ladislav (1944). Stará garda Národního divadla: Činohra-opera-balet [The Old Guard of the National Theatre: Drama, Opera, Ballet] (in Czech). Praha: Jos. R. Vilímek.

- ^ Otokar Fischer, Činohra Národního divadla do r. 1900. p. 108.

- ^ a b c Ludwig Hoffmann, Maria Pospischil, k.k. Hofburgschauspielerin. P. 28.

- ^ Slečně Marii Pospíšilové, In. Národni politika, Oct. 12 1890. p. 2.

- ^ Frâulein Pospischil, In. Die Bombe, June 22, 1890. P. 2

- ^ Im vollen Gegensatze…, In. Das Vaterland, Nov. 23 1890. p. 2.

- ^ Fräulein Adele Sandrock, In Münchener Kunst- u. Theater-Anzeiger, Mar. 1 1895. P. 3

- ^ Berliner Theater-Brief, In. Der Humorist, Sep. 1 1893. p. 3.

- ^ Maria Stuart’s Abschied, In Wiener Salonblatt, March 15, 1891. P. 7

- ^ Gutem Vernehmen nach, In Der Humorist, April 20, 1891. P. 3

- ^ Die internen Beziehungen, In Wiener Caricaturen, May 17, 1891. P. 3

- ^ In dem modernen Schauspiel Kriemhilde, In. Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, Nov 10 1892, p. 7

- ^ Wiener Burgtheater, In Allgemeine Zeitung, Jan. 19 1893, P. 1.

- ^ Frl. Maria Pospischil, In. Der Humorist, March 10. 1892. p. 3

- ^ a b Theater und Kunst, In Neues Wiener Journal, Sep. 4, 1894.

- ^ a b Ludwig Hoffmann, Maria Pospischil, k.k. Hofburgschauspielerin. P. 13.

- ^ Theater und Kunst. In Der Humorist. 1 April 1891. p. 2.

- ^ Wiener Theater-Revue. In. Osterreichische Musik- und Theaterzeitung, 1891 : Heft 19. p. 2.

- ^ Prager Brief. In Der Humorist. 2 May 1891. p. 91.

- ^ Ludwig Barnay, Erinnerungen von Ludwig Barnay. p. 425.

- ^ Melanie Hinz, Das Theater der Prostitution. p. 92.

- ^ Ignát Herrmann, Z poslední galerie, Divadelní kritiky Vavřince Lebedy II. p. 300.

- ^ Zpráva k mimořádné valné hromadě Družstva Národního divadla. p. 7.

- ^ a b c Milena Lenderová, K hříchu a k modlitbě. p. 222.

- ^ a b c Jaroslav Kvapil, Pohostinské hry slečny Marie Pospíšilovy. In. Zlatá Praha 1895, May 10, Nr. 26, P. 312).

- ^ Theater, In Kölnische Zeitung, 17 January 1895.

- ^ Fräulein Marie Pospischil. In. Münchener Kunst- u. Theater-Anzeiger, Jan 19 1895, P. 1).

- ^ Fraulein Mařenka Pospischil. Revue aus Böhmen. 14 January 1895. p. 3.

- ^ Konzert des Vereins Nikolai. Deutsche Musik-Zeitung. 1892/7. p. 61.

- ^ Čeští germanisté. Goethův sborník památce 100. výročí básníkovy smrti. P. 347.

- ^ Servác Heller, Rozmluva se slečnou Pospíšiilovou, In. Národní lisy. 1895/27. 27 January 1895. p. 5

- ^ Jan Herben, Čas, 1895/24.

- ^ Jan Herben, Čas 1895/9, No. 24. p. 373.

- ^ Původní dopis z Čech, In. Amerikán. 1895/34, 8 May 1895. p. 14.

- ^ František Adolf Šubert, Correspondence. Letter from 16 April 1895. Literary heritage in the archive of Památník národního písemnictví.

- ^ Viktor Dyk, Prsty Habakukovy. p. 186.

- ^ F. X. Šalda a.i., Rozhledy národohospodářské, sociální, politické a literární. 1895/7.

- ^ Vilém Mrštík, Paní Urbanová. p. 4.

- ^ Václav Štech, Džungle literární a divadelní. p. 41.

- ^ Hana Kvapilová, Marie Pospíšilová, In. Literární pozůstalost Hany Kvapilové, p. 217.

- ^ Výtržnosti v Národním divadle In. Pokrok západu. May 22, 1895, p. 16

- ^ Kateřina Urbanová Mojsejová, Profesní a soukromý život divadelních hereček od 60. let 19. století do roku 1918. p. 206.

- ^ František Adolf Šubert, Dějiny Národního divadla v Praze 1883-1900, p. 402.